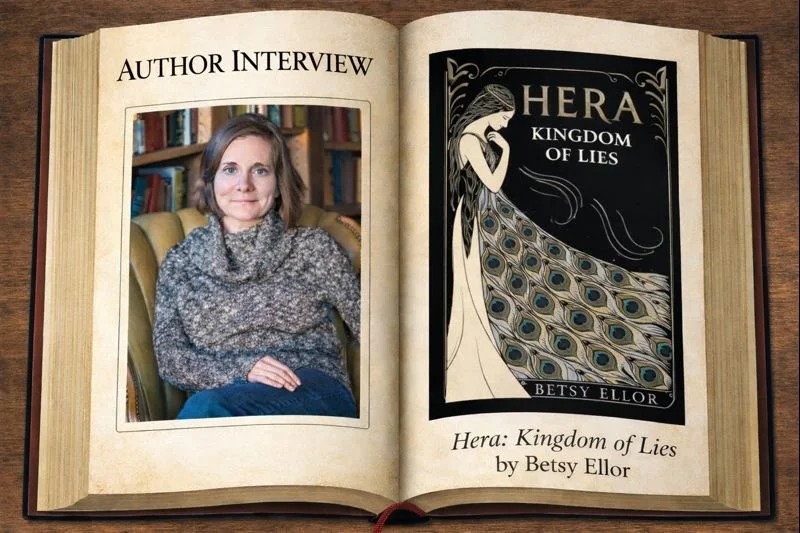

Interview with author Betsy Ellor

/Today our guest is author Betsy Ellor and is here to talk about her just released novel: Hera -Kingdom of Lies and a bit about her writing process and going the indie publishing route.

Congratulations Betsy on your debut novel Betsy, and welcome to Scribbler’s Ink. .

Can you share what first sparked the idea for this story?

For this novel, there were a few different sparks. I’ve always loved mythology, and after I became a working mom, my sympathy for Hera grew. Hera is usually portrayed as petty, jealous, vengeful, and also kind of a wet blanket to the other gods' games. I think any woman focused on their career, but also balancing all the pressures that go with raising a family, will empathize with there being more to the story than what’s on the surface. That was in my mind as I read the old myths, but the idea didn’t solidify into a story until I found out about the Heraion in Samos, Greece. This temple to Hera predates the myth of Zeus. When I realized that in ancient times, Hera was worshipped long before the rest of the Greek pantheon took shape, I had a million questions: What did that world look like? Why did it change? How did Hera feel about it? Those are the questions that lit the flame that became the story.

Women’s fiction often centers on relationships, growth, and inner change. What themes felt most important for you to explore in this story?

Hera is in soooo many of the Greek myths. I had a lot to sort through while developing the story. As I played around, I realized one theme kept resurfacing: how does a person balance who they are with what society expects them to be? Hera was assigned the role of overseeing the dominions of marriage and family, but she is married to a god defined by his infidelity. She is tasked with embodying perfect motherhood, but her first child is the literal God of War. What must he have been like to parent as a toddler? The conflict between her self-identity and the expectations placed upon her lead Hera to some bad choices on the journey to discovering who she is, how she wants to exist in the world, and how to claim her true power. While this setting is historical those themes still resonate today, especially with women who are trying their best to be professionals, mothers, friends, and wives when we are bombarded with media telling us conflicting information about what those titles mean.

Was there a particular character who felt especially close to your heart as you were writing?

What?! I can’t pick just one! Ok, if I must I’ll pick Panoptes. He is a mute giant with eyes all over his body. He crops up in the myths a few times to help Hera. (He is commonly referred to as Argos Panoptes, but Argos is also a setting in the story, so I simplified his name.) Panoptes is a quiet, fun-loving, and a solid, supportive presence for Hera. With every revision, his role grew because he is exactly the friend any of us would want by our side if we we going through a lot, like Hera does.

Did any scenes or moments surprise you as they unfolded on the page?

As with any retelling, you have a structure of moments you must stay true to, but I was constantly surprised by the ways I was still able to either flip a well-known story so it had a whole new interpretation or connect the old stories in a new way. I connected a character from one myth with an action from a different myth and have those two things interact to explain how a third myth came to be. It all stayed true to the original, but also created something new - sort of like doing a connect-the-dots, but out of order, resulting in a whole new, fresh picture.

Without giving anything away, what do you hope readers feel or reflect on when they reach the final page?

I hope they feel seen and inspired; also empowered to be ruled by their own inner compass and sense of identity rather than roles forced upon them.

What does your writing process look like? Are you a planner, a fly by the seat of your pants writer, or somewhere in between?

I usually write about 30-50 pages on instinct, letting whatever is trying to come out freely flow. By that point, I have a sense of what I’m trying to do, so I can create a loose outline. I find that if I outline too tightly too early, the work stops being fun. My first drafts are pretty bad, but I enjoy editing heavily to get the story where it needs to be.

What did a “good writing day” look like for you while working on this novel?

This novel was one of those unique gifts the muse gives out. I wrote the 130K word first draft in 3-4 months. That is not normal for me. If you are a writer, don’t read that and get discouraged. I was going through a stormy divorce at the time and had both a lot of emotions to tap into and a high-level need for the escape of writing. I was also only working part-time, so I was basically writing morning, noon, and night until my fingertips ached from writing. Nowadays, I write seven days a week, early morning for about an hour or so. A good writing day is usually when I can get half a weekend day to work on revisions without interruptions.

What was the most challenging part of writing this book, and how did you push through it?

Well, my first draft was 130K words, and I was pursuing traditional publishing, which typically wants a debut to be a stand-alone novel with under 100K words. I spent a lot of time squishing the story I was trying to tell down to fit into that box. After a year or so with lots of interest from traditional publishers that didn’t turn into a sale, I decided to indie publish. I printed it, read it and it felt rushed. It was obvious I needed to expand the story into a series. Starting basically over again was a big mountain to embark on, but I enjoyed going through and letting each moment expand. I got to create more world-building, let the characters feel all the moments in the story, to show more and tell less and to create a truly tightly interwoven plot. It was hard, but it was worth it.

For writers considering indie publishing, what’s the one piece of advice you wish you’d had at the start?

Know why you’re doing it. If you’re doing it to make money, that’s going to be a different list of things to do than if you just want to get the story out and have it connect with a few meaningful readers. Publishing and selling your work takes a lot of time, it can cost a lot of money if you’re not careful, and you will definitely feel pulled in a million directions. Knowing your why will be essential to guiding your choices, overcoming frustration, and letting you know when you’ve achieved your own definition of success.

Are you already working on another project or letting this one settle for a bit?

I’m already underway with Book 2 in this series, and hope to have that out early next year. I’ve done a few other projects in between, and I’m excited to get back to this world.

Betsy's Bio

Betsy Ellor is a women’s fiction author and multi-disciplinary creative whose work blends intrigue, myth, and magic with strong, complex female leads. Known for her tightly woven storytelling, she’s the editor of the anthology Heroic Care, author of the picture book, My Dog is NOT A Scientist, from Yeehoo Press, and scribbler of articles and stories for various outlets, including Spine Magazine, 5 Minute Lit, and The Creative Collective.

Links:

https://www.wordsunboundstudio.com

To order the book: